Orange Magazine

December 2007 / January 2008

Late Day, Winter Morning, oil/linen, 24x30

Sold Sold

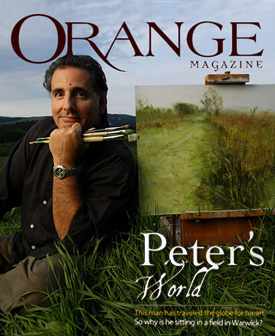

Artist Peter Fiore in Pine Island NY

|

|

Orange Magazine

December 2007 / January 2008

Peter Fiore: A Still Life

Waiting for Art to Reveal Itself

PETER FIORE drives from where he lives and works across the Delaware River in Pike County, Pennsylvania, and into northwest New Jersey, and pulls off to the side of a winding two-lane road. He walks into a field with bugs and birds and knee-high flowers and weeds. He’s come here to teach you to see.

IT'S LABOR DAY WEEKEND. The early afternoon wind blows and there’s just a small tinge of the coolness to come. The field is green on green with a small hill and three hawks circling up above the pines and the oaks and the elms and by the big puffy clouds in the blistering light of the high blue sky.

But by late October, early November, he says, all this starts to change. The sun gets lower, the green goes away, the leaves drop from the oaks and the elms, and the light hits the snow and shoots back up and the sky seems not quite so spotlight bright. The red wood barn pops out from behind the trees.

“In the winter,” Peter says, “the world gets sharp. Beautiful things happen.”

How do you learn to paint? You learn to see.

How do you learn to see? You learn to wait.

Peter waits until the early evening because that’s when the light is the best. He waits until the winter because that’s when the earth reveals the most. And that’s what this story is about.

Waiting.

FIORE IS THE SON OF A SICILIAN who ran a liquor store in the South Bronx back when it was tougher than it even is now. He grew up to become the president of the Society of Illustrators, and to do the art for a children’s book written by the wife of the vice president, and to live in a nice blue house on the Delaware with his wife, Barbara, and to work in a studio on his property that he built and in which he keeps a Mickey Mantle autographed baseball and his dad’s old shaving kit. His paintings can sell for as much as $18,000 apiece.

But first you have to kick this back a bit, like almost a half a century back, to when Peter is probably about two years old, he says, and his grandmother is living with them in the dining room of their apartment in the Bronx. The light from the chandelier hits her hair and turns it a white silver and it hits the table and makes the surface look like it can float. That’s his first memory.

So that’s the beginning.

Now it’s seventh grade, maybe eighth, at St. Michael’s school in Palisades Park, New Jersey, and there’s a question on an aptitude test. You’re on a train. Would you rather read a book, sleep, talk to people or look out the window? Easy. Look out the window. Which Peter does all the time in junior high. He watches how the wind hits the leaves of the trees outside. Stop daydreaming, the sisters say, and it’s partly true that that’s what he’s doing, but it’s also so much more.

His favorite subject is geometry. The study of shapes in space. His favorite sport is baseball. The game based on natural rhythms and moments in time but with no clock.

Now Peter’s about 12, summer vacation, and a man comes into the liquor store in the South Bronx, Al & Andy’s Liquors on 141st Street and St. Anne’s Avenue, and wants to trade a camera for a bottle of Wolfschmidt vodka. Mario Fiore makes a deal. He brings the camera home to Lodi, New Jersey, to his son. Here, he says.

Peter gets two dollars a week, too. One dollar for film, one dollar to get it developed. Thirty-six shots a week to keep learning how to see. He looks, through that Zeiss Ikon Contessa camera, at the way the light hits the old ivy-covered buildings at Felician College in Lodi and the nearby stream and his mother in the kitchen or his father home from work or his brother playing around. He learns dark room work and develops his own pictures. He puts the paper in the chemicals and watches that wet inky black and waits for his images to emerge.

Now Peter’s about 14, in the apartment in Lodi, and the door to his parents’ room is open. The light is coming through the window through the slightly parted heavy linen drapes, and on the beige bedspread on the unmade bed is a diagonal slash of warm, pink light. Peter takes the picture. A portrait of my parents, he thinks. A portrait of them without them being there.

Now he’s in his early 20s, in September 1976, he’s a student at Pratt Institute in Manhattan, and he and his brother are going to a Yankees game up in the Bronx. They’re outside the stadium and the orange light of the late afternoon in the early fall is making a shadow on the side of the structure. Peter tells his brother to look at the blue shadow. That shadow’s gray, his brother says. No, Peter says. Look harder. Wait. See it now?

A MONTH LATER, a Friday afternoon, and Peter sends samples of his illustration work from Pratt to McCall’s, Redbook, Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping and Woman’s Day. By Monday morning he has a $2,000 job from McCall’s.

The work from the women’s magazines starts to come, and keeps coming, and he drops out of Pratt at the end of the semester of the fall of ’76. He starts to make a living.

He does anything and everything. He does ads for Lacoste; murals for Polo; brochures for United Airlines; labels for coffee cans and ice cream companies; annual reports for camera, consulting and pharmaceutical companies; movie posters; posters of Pebble Beach for the United States Golf Association; record covers; covers for the American Journal of Nursing; covers of romance novels; covers of Agathie Christie mystery thrillers, and the art for Lynne Cheney’s bestselling book called When Washington Crossed the Delaware. It’s slick, tight stuff, and it sells.

He does this for most of his 20s. He does this for all of his 30s. He does this for most of his 40s. And he waits.

Awards come, lots of awards, but it feels repetitive. It feels empty. It’s not enough. So starting in October 2000, he doesn’t do much commercial illustration work anymore, hardly any, and he begins working on his landscapes with oil on canvas. A year and a half later, March 2002, he sells his first three paintings, to a doctor and his wife, out of the Greenwich Workshop Gallery in Fairfield, Connecticut. He and Barbara walk to an Italian restaurant in Fairfield, and he calls his kids “to tell somebody close,” he says.

Now, barely more than five years later, his paintings are in galleries in New Hampshire, New Jersey, Connecticut, Pennsylvania and Virginia. He’s just won first place for landscape in The Artist's Magazine annual competition, he's also won an honorable mention there. He's been a finalist in an Art Renewal Center competition and he’s won the Alden Bryan Award for Landscape from the American Artists

Professional League. Fine Art Connoisseur has praised his “compositional simplicity” and “lively brushwork” and called him “a standout.” There is in his work, the magazine says, “a touch of romantic nostalgia to empty spaces, without crossing that invisible border into sentiment or prettiness.” American Artist magazine, he says, wants to do a story.

And he’s done about 30 paintings off that field in northwest New Jersey. The cars race by while he stands still and watches the wind and the leaves and the light. “You get more by waiting than you do by moving,” he says. “You wait for the light to come and it will change the world in front of you.”

A picture of a red barn is a postcard, he says. The relationship between the light and that red barn? That’s a painting. The interaction between that relationship and the viewer of the painting, to create, perhaps, an essential truth, a universal moment, a feeling you’ve felt before, “a visceral response,” Peter says?

That’s art.

And that takes time.

Back in his studio, Peter keeps that Mickey Mantle autographed baseball, his dad’s old shaving kit, and pinned to the bulletin board is his acceptance letter to Pratt from 1973. He keeps most all of his old brushes, even when they have just a few hairs left, because he can use them to create the smallest, tiniest details. “When they get worn down,” he says, “that’s when they get interesting.”

He listens to Mike and the Mad Dog sports radio. When that goes off, though, he listens to classical music. Mozart died when he was 35 years old, and Beethoven died when he was 56, and the difference between Mozart and Beethoven, Peter says, is the difference between being perfect and being profound. Mozart is one of the great composers in the history of the world. But Beethoven got to grow old. Beethoven got to wait. “And Beethoven,” he says, “makes me weep.”

PETER FIORE HAS taught at Pratt, Syracuse and Delaware, and now he teaches at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan. He has this assignment he gives to his young students: He tells them to go somewhere to sit and to watch the light and to watch it change.

And to just sit there. And to just sit still. And to do that for three hours. What FOR? they always ask.

--Story by Michael Kruse

--Photos by Chris Ramirez

________________________________________________

More in Press More in Press

About Peter About Peter

Paintings Paintings

|